“Adhere to your own act, and congratulate yourself if you have done something strange and extravagant, and broken the monotony of a decorous age.” -Ralph Waldo Emerson

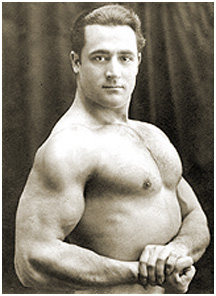

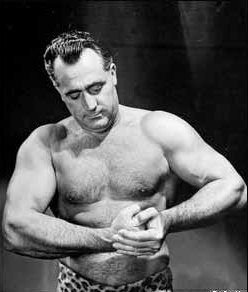

The story of Nick Piantanida is not the straightforward, unambiguously heroic tale of Joseph Kittinger. It ends in tragedy, not triumph. Piantanida did not accomplish what he sought to do, and he paid the ultimate price in the attempt. But still it was, as Craig Ryan, author of a book on Nick’s life puts it, a “magnificent failure.”

After all, it’s one thing to leap from space as part of an official program, with the resources and authority of the Air Force behind you. In his autobiography, Kittinger admits that he was the “luckiest man in the sky,” someone who was “in the right place at the right time.” Chuck Yeager said the same thing of the chances he got to achieve his amazing feats. Both had guts and skill in spades, but they also happened to be in the right place at the right time to seize the opportunities that came their way.

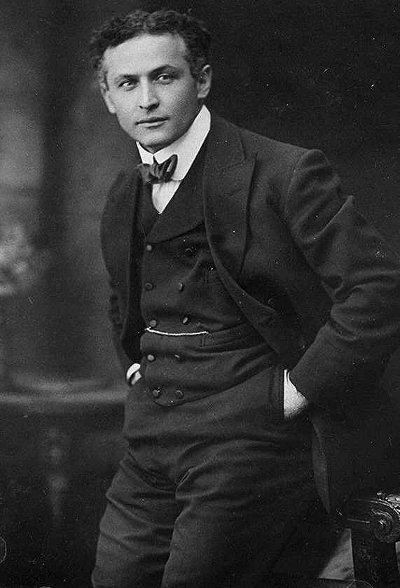

Where does that leave the ordinary man? Most guys would look at men like Yeager and Kittinger and think, “I’ll never be able to do something like that.” And this is where Nick Piantanida’s story provides a different sort of inspiration. Nick had no special resources or lines into his adventures; he simply made them happen himself by hustling like a crazy man. Here was an average joe, a truck driver from Jersey, a devoted Catholic and family man, who completely bootstrapped his way to within a hairbreadth of remarkable success.

Marching to His Own Beat

“I’ve heard him called a rebel. But Nick was never rebelling against anything. Nick was too busy. He had his own stuff going. And that’s where he was most of the time.” -A childhood friend

Nick Piantanida’s desire to push his limits and do so outside official channels started young. Whatever he wanted to learn, he set out to teach himself. In high school he taught himself karate and scuba diving. And when his high school basketball coach told him to put out a cigarette after a game, he quit the team and practiced at a neighborhood court by himself, every day, in every season, rain or shine. He played ball in various leagues on the East Coast and became one of the best players in the NY/NJ area.

After high school, Piantanida joined the Army and took up boxing. One night, while reading a men’s adventure magazine in the barracks, he found the idea for his first daring exploit. An article trumpeted the abundance of diamonds to be found in the impenetrable jungles of Venezuela, and Nick decided to go and check out the claim himself. But the lure of treasure was not enough-he wanted to also do something no man had done before. While looking for diamonds, he would try to become the first man to climb Devil’s Mountain, a giant mesa from which tumbled the highest waterfall in the world: Angel Falls.

To the Top in Venezuela

“Nick ad-libbed his life. He didn’t believe in scripts. He believed in himself. He was the ultimate survivor. If a piranha bit Nick, the piranha would die.” -Fred Cranwell, childhood friend

As soon as Nick got out of the Army, he began to set his plan in motion. He had very little money to his name, so he started talking to companies about potentially sponsoring his trip. With only a vague outline of how he was going to accomplish his goal and a powerful dose of charm, he was able to obtain an outboard motor from Euinrude, firearms from Colt, cameras and film from Kodak, and two tickets to Caracas from Grace Line Shipping.

There were a few things Nick had neglected to tell his sponsors, such as the fact that he and his expedition partner, Walt Tomashoff, had very little mountaineering experience and no experience climbing with ropes and carabiners whatsoever. But Nick did what he always did: he taught himself. He bought some rope and a book about climbing and practiced on the Hudson River Palisades above Hoboken, New Jersey. He and Tomashoff honed their climbing skills during the day and worked in a can factory at night to support themselves.

When the daring pair arrived in Venezuela, they learned to their dismay that another man, Aleksandrs Laime, had already summited Devils’ Mountain a few months prior. But Nick still wanted to grab a “first” and so decided to scale a route on the north side of the mountain which had never before been climbed successfully and which many considered simply unclimbable. The north side was the wet side where Angel Falls plummeted downwards. The men would be tasked with climbing parallel to a gushing, roaring beast which rose to a height fifteen times greater than Niagara Falls. Even getting to the bottom of the falls was a treacherous task. This was accomplished by paddling a dugout canoe down the Rio Carrao and Rio Churun, struggling for 3 weeks through 48 sets of rapids and fighting off insects, foul weather, and numerous injuries along the way.

Once at the base of the falls, the men began their ascent, a nearly vertical climb that required hacking through jungle so dense and gnarly it sometimes required 10-12 hours of toil to penetrate. Constantly both wet and hot (the daily temperature rose to 100 degrees and it would rain for hours on end) the men scaled the wet, muddy mountain face, grabbing onto to roots and vines. Nick’s cheap boots quickly rotted away from the intense moisture, forcing him to continue the climb in deteriorating Chuck Taylors strapped to his feet with cords. Laime, who had decided to accompany the pair, grew discouraged at their prospects and turned back. But Nick and Walt pushed on.

After several weeks and 3,212 feet of arduous climbing, Piantanida and Tomashoff made it to top just as their food was running out. The pair found neither diamonds nor much fame, but the thrill of chasing a record had left Nick hungry for another challenge.

Learning the Ropes…and the Chutes

“You can’t tell what moves you to do such things. That is just how I am. Most people talk about such things and do nothing. I just have to go and see.” -Nick Piantanida

When Nick returned to the States, he took a job in an embroidery factory and bounced around to different colleges playing basketball. He had brought back some exotic pets from Venezuela-parrots, lizards, snakes, and a small alligator which lived in his bathtub. After ordering a cobra from India and teaching himself how to handle it, he tried to start a company which procured exotic animals from around the globe for clients. He also worked on the Verrazano Narrows Bridge as an iron worker, took other odd jobs, got married, and started a family.

But it was while visiting the Lakewood Sport Parachute Center on the Jersey Shore that he found his life’s passion: parachuting.

These were the days when skydiving was in its infancy, a time before soccer moms and 80 year old ex-Presidents eagerly leapt from planes. These early parachutists used round army surplus chutes, which gave the jumper very little control or steering ability. Landing on one’s feet was a daunting task, and jumpers often broke bones and suffered other injuries as they tumbled back to earth. There were no rip-stop jumpsuits, no Velcro. When the parachute inflated, the harness pulled so hard it left big bruises on one’s groin and armpits. And equipment malfunctions-and fatalities-were all too common. The parachutists of this era were members of an elite, close-knit, wise-cracking fraternity, tough, daring SOB’s who lived for the thrill of falling from the sky.

All of which accounts for parachuting’s appeal to Nick. He was hooked after his very first jump and soon began hatching a plan to set the record for the highest, longest skydiving jump in history. The record then held by Joseph Kittinger.

Achieving this feat would be no easy task. Nick wasn’t a college graduate, and he had no connections to the Air Force or Navy, to research labs, or to the companies that made the balloon and pressure suit he would need for the jump. He would have to assemble each aspect of the project on his own.

Nick set out to learn and study everything he could about what the complicated and supremely dangerous endeavor would entail. He devoured every piece of information he could find. He had to understand the deadly conditions of the stratosphere, the physics and physiological effects of falling from 20 miles above the earth, and the nuances of the equipment he would need to reach space and return safely. As Craig Ryan put it, Nick “transformed himself into the director of a one-man aeronautical research program.”

Piantanida appealed to official channels for advice and information, writing to the Air Force and Navy for help, but the service branches wouldn’t give this crazy civilian the time of day. He appealed to Kittinger for advice, but the record-holder refused, feeling Nick’s approach to the project was too reckless.

Getting access to the right equipment was just as challenging as getting his hands on information. He needed a pressure suit and a huge balloon, but private companies only contracted with the military and wouldn’t deal with a private citizen.

And of course Nick needed money. It would cost $120,000 a jump for the equipment and support crew, and Nick didn’t have a deep-pocketed corporate sponsor like Red Bull footing the bill. So he sent out thousands of letters to ordinary citizens asking for donations. He found men willing to be part of his ground crew as volunteers, and he asked hotels and restaurants to lodge and feed the crew in exchange for potential publicity. He hit up any reporter he could find to help him get the word out. His local priest reached out to parishioners for donations. He had his Senator doggedly appeal to the military on his behalf. With unflagging determination and a magnetic, larger than life personality his only resources, Nick worked every angle and connection he could think of.

While he waited for the funding and equipment to come through, Piantanida trained like a mad man. In two years he made 435 skydiving jumps, criss-crossing the country to take advantage of rare opportunities for higher-altitude jumps. He worked to obtain his free-balloon pilot’s license. To make ends meet he drove trucks at night and jumped during the day. He worked 7 days a week on the project, only allowing himself 4 hours of sleep a night and imbibing coffee and cigarettes for breakfast.

Nick had no back-up plan for his life. He was determined to make it big with a record-setting jump and to parlay that success into a good life for his family. Even though he faced rejection after rejection and numerous setbacks, his enthusiasm and belief in his eventual success never diminished. The idea of failure never crossed his mind. He would find a way to make it happen.

Project Strato-Jump

“He was always a little bit over-eager, a little bit on the reckless side. Full head of steam, pedal to the metal. That was Nick. If you went with Nick to have a beer, you’d have six beers. Life to the fullest. That’s the way he did everything, that’s the kind of life he lived. I mean, if you’re going to go climb Angel Falls you can get down there and take a look at the thing and think of fifty reasons why you’re not really ready to do it. But you wouldn’t be Nick if that were the case. And I think today that’s really hard for people to understand, because we’re in such a safety-mad universe.” -Roger Vaughan

Eventually Nick’s dogged persistence paid off. He obtained some sponsorships. The Air Force allowed the David Clark Company to loan him a pressure suit and offered some of their training facilities to practice in. He found a solid team to back him up on the ground. After two years of pure hustle, Nick’s dream was finally coming together.

The goal was to set the new skydiving record (and make some scientific progress in the process) by jumping from a balloon floating from 115,000 feet above the earth. This was Project Strato-Jump.

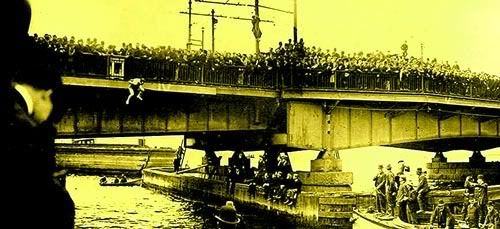

Strato-Jump I, October 22, 1965: Nick’s first jump attempt was a bust. His balloon malfunctioned just 18 minutes into flight, forcing him to bail out at only 16,000 feet. With the press watching, Nick ingloriously touched down in a trash dump. Nick had envisioned Strato-Jump as a one shot deal-he would set the record on the first go around. He was deeply disappointed but immediately decided to regroup, raise more money, find a new balloon company, and do it again.

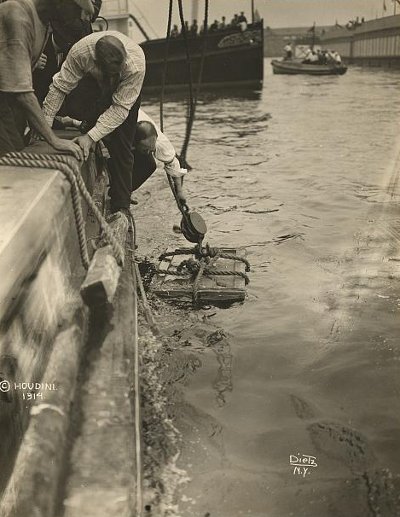

Project Strato-Jump II, February 2, 1966: On a frigid morning in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Nick’s balloon rose into the sky with hardly a hitch. Everything was going to plan as it climbed higher and higher, soaring all the way to 123,500 feet (21.21 miles) above the earth. Nick had obtained the new world altitude record. Success was at hand. Now it was time to jump. Nick removed his seat belt and prepared to make his record breaking leap.

There’s was just one more thing to do-disconnect the hose that fed oxygen from the gondola into his pressure suit. Simple. But it wouldn’t come out. Right at the edge of success and he was tethered to his gondola. “I just can’t believe it!” he kept saying.

The get Nick down, the ground crew was going to have to jettison the gondola’s main balloon and allow the capsule to fall to earth beneath the cargo chute that sat underneath the main balloon. No one had ever attempted to land a human in that way. Ground crew ordered Nick to reattach the belt that stretched across the capsule door and his seat belt in preparation for his return to earth. But the gloves of his pressure suit were so large that this was an impossible task. He would have to simply wedge and brace himself inside the open gondola, hoping that the inevitable jolt when the cargo chute opened would not eject him into space or rip the oxygen tube from his pressure suit.

When the balloon was released, the gondola, with its door open, tipped forward at a 45 degree angle, but Nick hung on. He dropped for 25,000 feet, speeding towards the earth at 600 mph. After 15 seconds of freefall and 5 g’s of force, the cargo chute finally inflated.

He landed in one piece but was devastated his dream had been derailed by a little “quick disconnect” tube, a problem he felt could have been solved with a “$1.25 wrench.” He had set the new altitude record for manned balloon flight, but that didn’t matter. His dream had not been realized.

Project Strato-Jump III, May 1, 1966: Nick started dreaming about new projects and endeavors and according to Ryan no longer felt as “personally driven to make a third flight.” But his sponsors and ground crew remained enthusiastic and hopeful, and he told his wife that “he had promised the public a third Strato-Jump flight and he felt honor-bound to make good on his word.” He swore that no matter what the result of this last attempt, it would be his last try.

So on an early Sunday morning in 1966, Nick found himself rising above the earth for the final time. He and the ground crew felt supremely confident; Nick promised to be up and back in time for 11:00 Mass.

Just as in the second flight, things seemed to be going very smoothly. Everything was on track.

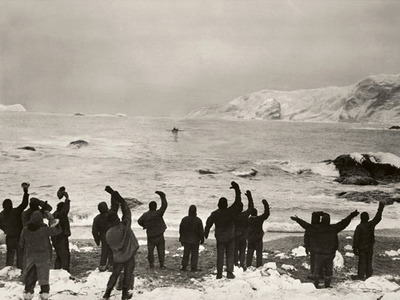

But as the balloon neared 57,000 feet the ground crew heard a sudden “whoosh” sound come over their radio. “What was that Nick?” they radioed back nervously. “Emergen….!” was the only reply. The radio transmission went dead.

Ground crew immediately jettisoned the main balloon. Just as in the second flight, Nick would return to earth swaying beneath the cargo parachute. It took 26 excruciating, silent minutes for the gondola to touch down in Minnesota. Nick was found moaning but unconscious. He was rushed to the nearest hospital where unfortunately doctors had no experience dealing with high-altitude decompression.

Brain damaged beyond recovery, Nick lingered on for four more months but never emerged from his coma. He died August 25, 1966 at the age of 34.

What had happened to Nick at 57,000 feet? There have been plenty of theories advanced and debated through the years. The most likely scenario is that Nick inexplicably lifted the visor of his helmet, and the sudden decompression and loss of oxygen quickly did him in.

Nick Piantanida’s altitude record for lighter-than-air flight has stood for more than 35 years. He was the last man to take a balloon into the upper stratosphere.

Legacy

“Where is the line between courage and folly?” Craig Ryan asks. Was Nick a reckless daredevil? His jumps were never about the thrill; he genuinely wished to aid scientific progress, to push the limits of what was out there, and to accomplish something no other man had done. Did he prepare enough? He did the best an ordinary civilian could have but inevitably lacked the opportunities for rigorous testing and the access to the very best and most experienced minds in the field.

What are we to make of a man like Nick? Was his inability to admit the risk of failure, and the chance he might leave his children fatherless a form of hubris? Or should we cheer his adventurous spirit, DIY effort, and manful demonstration that great daring is not reserved for the loners or the lucky?

Ryan neatly sums up the inevitable tension we experience as we weigh such questions:

“Nick Piantanida represents a quality we profess to admire: the unquenchable drive to exceed, to surpass, to fight on to the end. Yet the individuals who would take up that quest often make us uncomfortable. Why aren’t they content to recognize the limits that constrain the rest of us? What are they trying to prove?

When pioneers return from the frontier, we revere their risk-taking, their perseverance, their courage. When they become lost in the wilderness or are defeated by the elements, we shake our heads and curse them for their foolhardiness, their irresponsibility-and yet the difference between success and failure in such ventures is often a mere hairline…’Splendor and folly are so near to each other. Indeed, we can barely tell one from the other, so much alike are they, and so close the line between glorious fulfillment and crushing frustration.’

Nick Piantanida’s last shot at the stratosphere will be remembered, finally, as a magnificent but failed attempt to extend the front lines of humankind’s advance into that ultimate frontier…It was truly, to use Jim Winker’s cautiously enlightened phrase, ‘an attempt of the human spirit to do something remarkable.’”

If you missed it, read Part 1: Joseph Kittinger’s Long, Lonely Leap.

Source: Magnificent Failure by Craig Ryan. Ryan has written books on the “pre-astronauts” and Kittinger and Piantanida. All are excellent and highly recommended.

Despite the fact that Bob Ewell “won” the case against Tom Robinson, he held a grudge against everyone who participated in the trial for revealing him as a base fool. After the trial, Ewell threatened Atticus’s life, grossly insulted him and spat in his face. In response, Atticus simply took out a handkerchief and wiped his face, prompting Ewell to ask:

Despite the fact that Bob Ewell “won” the case against Tom Robinson, he held a grudge against everyone who participated in the trial for revealing him as a base fool. After the trial, Ewell threatened Atticus’s life, grossly insulted him and spat in his face. In response, Atticus simply took out a handkerchief and wiped his face, prompting Ewell to ask:

If Atticus had one dominating virtue, it was his nearly

If Atticus had one dominating virtue, it was his nearly  Atticus is probably best remembered as an exemplary father. As a widower he could have shipped his kids off to a relative, but he was absolutely devoted to them. He was kind, protective, and incredibly patient with Jem and Scout; he was firm but fair and always looking for an opportunity to expand his children’s empathy, impart a bit of wisdom, and help them become good people.

Atticus is probably best remembered as an exemplary father. As a widower he could have shipped his kids off to a relative, but he was absolutely devoted to them. He was kind, protective, and incredibly patient with Jem and Scout; he was firm but fair and always looking for an opportunity to expand his children’s empathy, impart a bit of wisdom, and help them become good people.

“Nature has not intended mankind to work from eight in the morning until midnight without that refreshment of blessed oblivion which, even if it only lasts twenty minutes, is sufficient to renew all the vital forces.”

“Nature has not intended mankind to work from eight in the morning until midnight without that refreshment of blessed oblivion which, even if it only lasts twenty minutes, is sufficient to renew all the vital forces.”

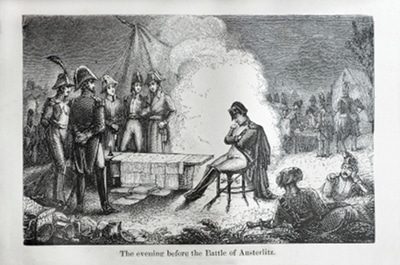

During campaigns, Napoleon was a whirlwind of energy, galloping from place to place, poring over maps, and pondering strategy. He would go days without changing clothes or lying down for a full night’s sleep. But he had the ability, as many great leaders do it seems, of being able fall asleep at the drop of a hat. This ability was likely a product of his supreme confidence. Napoleon could sleep like a baby right before battle and even when cannons were booming nearby. As they have been proven to do by modern science, Napoleon’s naps staved off the fatigue which stalks those who skip a whole night’s sleep. Then, when the storm of battle was over, the general would sleep for an eighteen hour stretch.

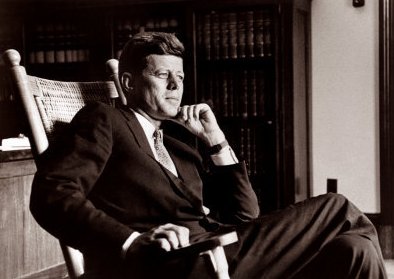

During campaigns, Napoleon was a whirlwind of energy, galloping from place to place, poring over maps, and pondering strategy. He would go days without changing clothes or lying down for a full night’s sleep. But he had the ability, as many great leaders do it seems, of being able fall asleep at the drop of a hat. This ability was likely a product of his supreme confidence. Napoleon could sleep like a baby right before battle and even when cannons were booming nearby. As they have been proven to do by modern science, Napoleon’s naps staved off the fatigue which stalks those who skip a whole night’s sleep. Then, when the storm of battle was over, the general would sleep for an eighteen hour stretch. After a mid-morning stint of swimming and exercise, John F. Kennedy would eat his lunch in bed and then settle down for a nap. He would have his valet draw the drapes and ask not to be disturbed unless it was a true emergency. He would then quickly fall asleep for a 1-2 hour nap. Jackie would always join him no matter what she was doing when her husband’s nap commenced, leaving an assistant to entertain her guests. Head of the household staff, JB West, recalled that “during those hours the Kennedy doors were closed. No telephone calls were allowed, no folders sent up, no interruptions from the staff. Nobody went upstairs, for any reason.”

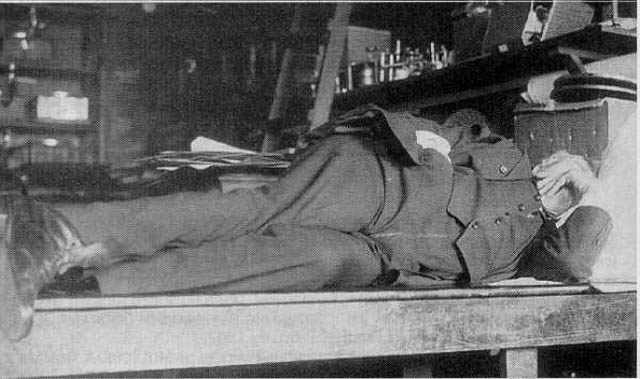

After a mid-morning stint of swimming and exercise, John F. Kennedy would eat his lunch in bed and then settle down for a nap. He would have his valet draw the drapes and ask not to be disturbed unless it was a true emergency. He would then quickly fall asleep for a 1-2 hour nap. Jackie would always join him no matter what she was doing when her husband’s nap commenced, leaving an assistant to entertain her guests. Head of the household staff, JB West, recalled that “during those hours the Kennedy doors were closed. No telephone calls were allowed, no folders sent up, no interruptions from the staff. Nobody went upstairs, for any reason.” Thomas Edison was something of a self-hating napper. He liked to boast about how hard he worked, how he slept only three or four hours a night, and how he would sometimes work for 72 hours straight. But in truth the key to his spectacular productivity was something he was loathe to mention and hid from others: daily napping. Once when

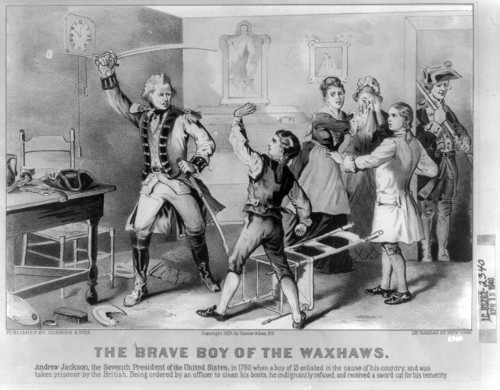

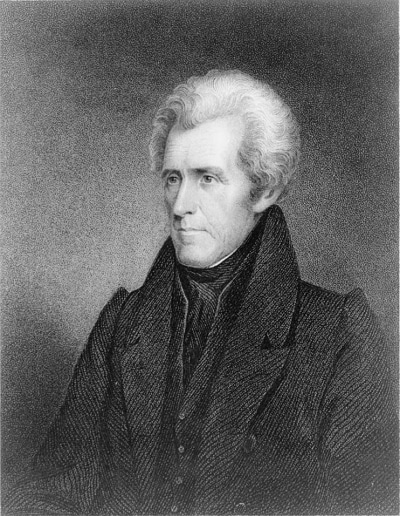

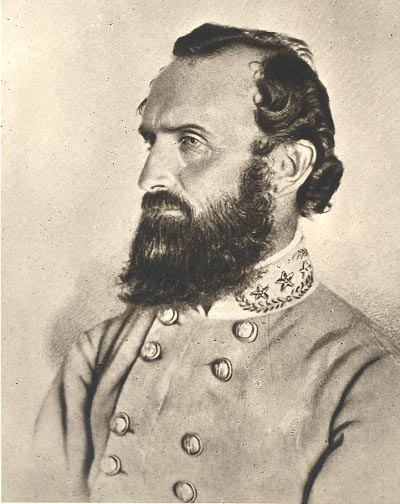

Thomas Edison was something of a self-hating napper. He liked to boast about how hard he worked, how he slept only three or four hours a night, and how he would sometimes work for 72 hours straight. But in truth the key to his spectacular productivity was something he was loathe to mention and hid from others: daily napping. Once when  Jackson, a general cut from the same cloth as Napoleon, could nap in any place—by fences, under trees, on porches–even in the stress of war. He liked longer naps but also had the reputation for taking quick, 5 minute siestas to rest his eyes. A couple of anecdotes of the General’s napping habits from A Thesaurus of Anecdotes of and Incidents in the Life of Lieut-General Thomas Jonathan Jackson by Elihu Rile:

Jackson, a general cut from the same cloth as Napoleon, could nap in any place—by fences, under trees, on porches–even in the stress of war. He liked longer naps but also had the reputation for taking quick, 5 minute siestas to rest his eyes. A couple of anecdotes of the General’s napping habits from A Thesaurus of Anecdotes of and Incidents in the Life of Lieut-General Thomas Jonathan Jackson by Elihu Rile:

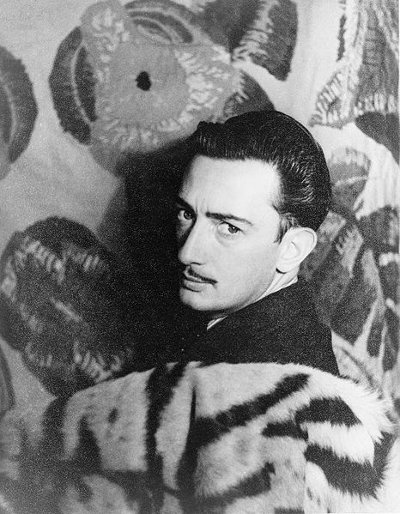

Eccentric artist Salvador Dali believed that one of the secrets to becoming a great painter was what he called “slumber with a key.” “Slumber with a key” was an afternoon siesta designed to last no longer than a second. To accomplish this micro nap, Dali recommended sitting in a chair with a heavy metal key pressed between the thumb and forefinger of the left hand. A plate would be placed upside down on the floor underneath the hand with the key. The moment Dali fell asleep, the key would slip from his finger, clang the plate, and awaken him. Dali believed this tiny nap “revivified” an artist’s whole “physical and physic being.”

Eccentric artist Salvador Dali believed that one of the secrets to becoming a great painter was what he called “slumber with a key.” “Slumber with a key” was an afternoon siesta designed to last no longer than a second. To accomplish this micro nap, Dali recommended sitting in a chair with a heavy metal key pressed between the thumb and forefinger of the left hand. A plate would be placed upside down on the floor underneath the hand with the key. The moment Dali fell asleep, the key would slip from his finger, clang the plate, and awaken him. Dali believed this tiny nap “revivified” an artist’s whole “physical and physic being.”