![walter cronkite on television gravitas]()

Word count: ~10,000

Time to read: ~45 minutes

In ancient Rome, four virtues were considered the chief pillars of excellent manhood and worthy leadership — none of which have a single word in English that entirely encapsulates their full meaning: pietas (duty, religiosity, loyalty), dignitas (dignity, status, influence, prestige), virtus (valor, manliness, excellence, courage, character), and gravitas (weight, seriousness, dignity, importance).

Of these four celebrated virtues, the last is the one that has found its way into our modern language in its ancient, unaltered form — we still speak of such and such a man as having real gravitas.

This is likely no coincidence, as the trait in many ways encompasses the other three, and is acutely needed in times of instability, uncertainty, and superficiality. For the Romans, gravitas denoted a man’s metaphorical “heaviness” — a strength of purpose, sense of authority, depth of character, and commitment to the task at hand that together formed a structure sturdy enough to bear the weight of his significant responsibilities. A man with gravitas held a position of importance, and used his influence to further the public good. His seriousness, his substance, acted as a counterbalance to all that was fickle, cheap, crass, disposable, flighty — those currents that have only grown stronger in Western society as time has gone on.

Though we may still use the word gravitas, and crave its greater presence in private citizens and public figures alike, beyond lists of its attendant qualities, it’s still a virtue that’s hard to describe. Like other weighty concepts, you know it when you see it, and it’s easiest to grasp in the illustration of someone else’s example.

Who then, is a good exemplar of gravitas to study? For me personally, there’s always one man who first comes to mind: Walter Cronkite.

As a radio reporter, newspaper journalist, television broadcaster, and special correspondent, Cronkite covered the world’s events for over six decades. But it was his nearly twenty-year stint as the anchor of the CBS Evening News for which he is best remembered. Each night for nearly two decades, his fatherly visage and authoritative, reassuring voice beamed into millions of households across America, comforting families’ grief during the assassination of JFK, steadying their nerves as astronauts first landed on the moon, and answering their questions about Vietnam.

Cronkite was called “The Most Trusted Man in America” after a survey found that he was, well, the public figure people trusted most. His presence was so constant, his demeanor so even-keeled, his warmth so genuine and paternal, he was also that rare figure whose name people take to prefacing with “Uncle.” Rarer still, Uncle Walt was respected by folks on both sides of the political aisle, and by those of all ages — from WWII GIs to Vietnam protesters. Many all across the country could identity with the sentiment voiced by Jack Paar, television host and one-time rival to Cronkite, who confessed: “I’m not a religious man. But I do believe in Walter Cronkite.”

What was the secret to Uncle Walt’s distinct gravitas? Why was his dignified presence such a centering force? How did he manage to command respect from such a wide spectrum of people?

Today we’ll answer these questions and take a look at Cronkite’s life as a case study in the kind of gravitas every man should emulate, and look for in their leaders.

Gravitas = An Unadulterated Core of Integrity, Surrounded by Layers of Tempered Rock

“At a time when everybody was lying — fathers, mothers, teachers, presidents, governors, senators — you [Cronkite] seemed to be telling them the truth night after night. They didn’t like the truth, but they believed you at a time when they needed someone to believe.” –Fred Friendly, President of CBS News (1964-66)

At the heart of the nature of gravitas lies a paradox. The trait denotes weight and heaviness, which conjures up the image of a rock. And there indeed must be something immovable about a man who possesses this trait — a pillar of integrity formed at the core of his character. But gravitas cannot be built entirely on dense, impervious stone. The relationship between seriousness and gravitas does not lie on a J-curve, but rather eventually reaches a point of diminishing returns.

A man who is too stiff, in fact becomes more brittle; his rigidity makes him prone to fracture; his one-dimensionality diminishes his weight — increasing his shallowness rather than his substance. A man who descends into unadulterated graveness, who takes himself too seriously, to the dissolution of any self-awareness, eventually becomes ridiculous.

This is the central lesson that emerges from studying Walter Cronkite’s gravitas.

At the center of his character was a strong sense of honesty and integrity — an undeviating moral compass — as well as an air of dignity and gentility. He was well-mannered, even courtly in his behavior. And this was as true of his on-screen personality as his off-screen one; those who knew him observed that he was the same man in all situations.

Cronkite’s friend Mickey Hart, drummer for the Grateful Dead (as we’ll see, his surprising relationship with Hart points to the fact there was more to Cronkite than the serious newsman), said of Uncle Walt: “I found Walter to be a real classy, straight-up gent…My father was a common crook. Walter became the father I never had…Walter walked the walk as well as talking the talk.”

Texas Monthly bestowed on him “a kind of innate, Calvinist honesty that can’t be manufactured or affected, and certainly not perverted.”

When one of his close friends was regularly asked what Cronkite was really like, he’d always answer: “He’s just the way you hope he is.”

And when the comic Dick Cavett was tasked with roasting him at an event, he admitted to the difficulty of the task, owing to the paucity of material to work with. “I’m taking the easy way out,” he told the audience. “I’m going to use all the jokes I used at the Mother Teresa roast.”

In truth, Cronkite wasn’t a saint. Nor was he a monolith of sober solemnity. And this was in fact the key to his distinct gravitas. Around the principled, ethical core of his character, were still other layers of substance — but layers tempered with qualities of lightness, humility, and flexibility — qualities that paradoxically enough, as we will see, added, rather than detracted, from his weight and clout.

Let’s now take a look at the pairs of counterbalancing traits that must each be in place for gravitas to develop.

Take Your Job/Role Seriously…

![walter cronkite at news desk on tv]()

“Cronkite can be terribly intense, and he’s very serious about his broadcasts. He’s not one for kidding around.” –Walter Schirra

“There are better writers than me, better reporters, better speakers, better-looking people and better interviewers. I don’t understand my appeal. It gets down to an unknown quality, maybe communication of integrity. I have a sense of mission. That sounds pompous, but I like the news. Facts are sacred. I feel people should know about the world, should know the truth as much as possible. I care about the world, about people, about the future. Maybe that comes across.” –Walter Cronkite, after being asked to explain his appeal

At the very crux of gravitas is a weight and depth of mind, character, and purpose. A man with gravitas shoulders serious responsibilities, and he takes these responsibilities seriously.

Walter Cronkite brought this “heaviness” to his role as a newsman. With integrity, a strong work ethic, and a desire to get things right, he carried himself as a real professional. He understood and embraced the significance of his role in the culture, and not only intentionally sought the cultivation of greater authority, but strove to direct that influence in a positive direction.

The ways in which he did this took a variety of forms:

Have a purpose/mission. As a high school student and the sports editor of the campus newspaper, Cronkite gleaned journalism lessons in economy, efficiency, and most of all accuracy from a teacher and former reporter who left an indelible impression on the budding newsman. “I had a sense,” Cronkite said of this mentor, “whenever I was in his presence that he was ordering me to don my armor and buckle on my sword to ride forth in a never-ending crusade for the truth.”

For the rest of his life, Cronkite saw the business of the “fourth estate” through similarly idealistic eyes — as less of a business at all than a kind of civic service essential to the maintenance of a well-functioning democracy. He saw journalists as having the weighty responsibility to act as a hedge against totalitarianism by presenting citizens with objective, factual, well-investigated information.

To accomplish this purpose, Cronkite believed, the media had to uphold high standards of dignity, accuracy, and intelligence. And he considered the greatest achievement of his long and storied career to be his contribution towards doing just that.

Cronkite worked as a reporter in print, radio, and television, and the latter two news sources were just coming of age as he was. As fledging mediums, it was not initially clear how they were going to be used and what kinds of forms and norms the news would take through these channels. Each was initially met with a good deal of not unwarranted skepticism, as the first news broadcasts on both television and radio tended to be short and shallow — a mere parroting of the headlines created by the “real” journalists working at the newspapers.

Having spent over a decade cutting his journalistic teeth as a wire reporter for the United Press, Cronkite took it as his mission to infuse print journalism’s long-established standards into these new mediums, helping to steer first radio, and then television, in a more substantial direction.

In his pioneering role as television broadcaster, he sought to counter the perception of anchormen as pretty boy ventriloquists who simply repeated the news that had been gathered by paper journalists and handed to them to read. Unlike his rivals at NBC, Cronkite insisted on maintaining more control over his broadcasts; working as both anchorman and the managing editor of the CBS Evening News, he not only voiced the content of the program, but stayed involved in its gathering and editing, allowing him to push for longer and meatier coverage of important stories.

Cronkite worked as a war correspondent on the ground in Europe during WWII, and if there was anything the experience had taught him, it was that the news could be used for good or ill — as an outlet for authoritarian propaganda, or an enhancer of civic education. Cronkite dedicated his life to trying to position journalism — even the televised variety — towards the latter purpose.

Choose principles over popularity. Douglas Brinkley, Cronkite’s biographer, argues that “competitiveness” was the anchorman’s “defining quality.” He wanted to be the first to break stories, and was driven to make the CBS Evening News the number one evening news program in the country.

But, at the same time, he steadfastly opposed allowing a drive for ratings, and the hunger for profit, to become an excuse for the compromise of principle.

When it came to breaking stories, his motto was “Get it first, but first get it right.”

Cronkite had made the decision to resolutely adhere to this code way back at the very beginning of his career, as is well illustrated by an anecdote Brinkley shares from young Walt’s days as a 19-year-old radio reporter:

“One day the wife of his boss, Jim Simmons, called the station to report that three firemen had been killed in a blaze in her neighborhood. Simmons rushed to Cronkite’s desk, saying, ‘Get on the air with a flash! The new city hall is on fire, and three firemen just jumped to their deaths!’ Cronkite, full of protestations and litanies, insisted on checking the facts himself with the fire department by telephone. ‘You don’t have to check on it,’ Simmons snapped at Cronkite. ‘My wife called and told me.’ ‘I do too have to check on it,’ Cronkite said, remembering the fundamentals of journalism instilled in him at San Jacinto High, The Houston Press, and INS. ‘Are you calling my wife a liar?’ a ticked-off Simmons asked the young Lone Star hotshot. ‘No,’ Cronkite said, evoking the Standard Model of Professional Journalism. ‘I’m not calling your wife a liar, but I don’t know the details.’ Simmons was now livid. ‘I’ve told you the details. The new city hall building’s on fire, and three firemen have jumped.’ With Cronkite resolutely refusing to go on air, Simmons, in a temperamental snit, headed to the microphone himself. Playing the fool, he went on the KCMO airwaves ad-libbing a breaking news bulletin about the supposedly burned firemen. Cronkite’s sleuthing subsequently proved that the fire had been minor. There were no deaths. Nevertheless, the next day, Cronkite was summarily fired by the ego-bruised Simmons.”

Rather than being crestfallen, the budding reporter was proud of being canned for sticking to his ethical guns, and carried these same principles forth throughout the entirety of his career. Cronkite ever after chose caution over acclaim, even if it meant another network beat him to a story.

And even if that story was one of the biggest of the century.

On the afternoon of November 22, 1963, reports began coming into the CBS newsroom that President John F. Kennedy had been shot by an assassin in Dallas. Although Cronkite desperately wanted to get into the studio and begin broadcasting the news, the camera wouldn’t be ready to begin rolling for at least twenty minutes. So, while the camera was made operational, CBS decided to break into the soap opera then airing — As the World Turns — with “bumper slides” announcing a news bulletin, over which Cronkite would read an audio-only announcement.

Around 2:00 PM EST more bulletins arrived in the newsroom, containing further details on President Kennedy’s condition.

By this time, the camera was ready, and Cronkite had taken his seat at the newsroom’s anchor desk. He threw out the feed to a reporter from a local affiliate station in Dallas, who gave an unofficial report that JFK was dead; he later repeated this pronouncement, saying it had come from a good source.

Cronkite, however, did not affirm the report himself.

The anchorman then received reports that priests had administered the last rites to the president. These were followed by several more bulletins carrying the news that Kennedy had died, including one from CBS’ own correspondent, Dan Rather. CBS Radio News considered his report official enough to declare the president’s passing.

But Cronkite did not.

More such “death flashes” came in over the wire, including dispatches that cited the word of one of the priests who had been at JFK’s bedside and government sources in D.C. Such reports were considered sufficient by ABC news to officially announce the death of the president.

Yet Cronkite continued to hold off.

It was not until 2:38 PM EST, when he received a flash from the Associated Press — a source he considered sufficiently authoritative — that the CBS anchorman made the official announcement that JFK had died.

Cronkite’s abundance of caution in making the pronouncement was born of his conviction that facts must be checked at least thrice over — and in the case of such a monumental story, even more times than that. The public was seized with anxiety, and conspiracy theories were running wild; Cronkite did not want to add to the tumult by spreading potential misinformation; his job was to cut through the chaos, not inflame it.

Cronkite’s commitment to discretion continued in the days that came after. He vetoed the idea of airing a re-creation of the shooting a CBS reporter had staged by buying a rifle similar to Oswald’s and positioning himself in the same Book Depository window in which the assassin had fired his deadly shots, and Cronkite further nixed the running of footage taken in the blood-soaked operating room where surgeons had tried to save Kennedy’s life. He considered both proposed pieces as overly sensational, macabre, insensitive to the grieving family of the slain president, and insufficiently newsworthy.

After Cronkite retired as an anchorman in 1981, he spent the next two decades watching in dismay as such lurid gimmicks became the common stock and trade of television news programs, and the standards he had worked so hard to erect over the course of his career steadily eroded.

In the twilight of his life, he regularly inveighed against the rising world of “newstainment” — marked by the single-minded chasing of ratings and its attendant trafficking in gossip over real facts, feel-good stories over hard news, editorializing over objective coverage, dumbed down snippets over meaty features, angry shouting over dignified delivery. “What I rail against,” Cronkite declared, “is the Action news, Eyewitness news” — the kind of “format that diminishes the importance of the story itself in favor of presentation.” He likewise lamented the effect such a format had on the public discourse — the way in which politicians had increasingly begun to speak in soundbites that would play well on such superficial “news” programs; “Naturally,” the veteran anchorman observed, “nothing of any significance is going to be said in 9.8 seconds.”

The problem, Cronkite believed, was that modern news organizations were beholden to their stakeholders, who were motivated only by profit, rather than by any sense of greater public responsibility — by any sense of higher purpose.

![walter cronkite working sorting through papers at news desk]()

Do your homework. A man with gravitas doesn’t talk out of his arse, but knows of which he speaks. Further, his grasp of knowledge is so solid, that he is able to clearly distill, interpret, and explain vital information to others.

When would-be television journalists asked Cronkite for advice on how to find success in the field, the advice he gave was to “Read, read, read.” He thought every newsman had to be eminently well-informed and know something about just about everything, from politics and science to music and sports. He himself was a voracious reader, who was particularly well-versed in American political history.

The field Cronkite really boned up on, however, was military aviation and aerospace technology. He decided to make the space race his beat, and become journalism’s authority on the world of jets, missiles, and rockets. To this end, he pumped government contacts for information, accepted the tutelage of meteorologists and aeronautical engineers, staked out Cape Canaveral, and even read sci-fi novels in order to catch not just the nuts and bolts of aerospace, but a vision of its future potential and cultural meaning. Particularly before the launch of the Apollo 11, Cronkite immersed himself in the details of its spectacularly unprecedented mission to the moon. “Never before had I seen Dad with such thick binders,” his son recalled. “We all knew he was studying like never before.”

![walter cronkite at nasa with space engineer]()

Though he never graduated college (dropping out after his sophomore year), and in fact failed physics while a student at the University of Texas, this autodidactic education gave Cronkite such a deep understanding of the mechanics of space-bound rockets that he was able to impart his hard-earned knowledge to the American public — who struggled to grasp the intricacies of this almost miraculous feat of human engineering — in a thoroughly accessible way. It was an ability even the passengers on those spacecraft appreciated. As astronaut John Glenn recalled:

“Space travel was so new that most people didn’t know how to relate to it. They understood an Indy driver because they knew how to turn a steering wheel right or left. Walter’s gift was helping the public understand the science of space. He was a teacher. His CBS broadcasts were the main factor in the public understanding my mission.”

As Brinkley puts it, “Cronkite was able to break down aerospace concepts for the average American without dumbing them down.” And he was able to offer his explanations on the fly, ad-libbing his commentary as rockets launched in real time. As Cronkite told the Chicago Daily News in 1965, this knack came down, once again, to intensively doing his homework:

“I don’t attempt to commit anything to memory, but somehow it gets there. I learn by doing; I don’t learn by reading. I’ve been to the basic sources and tried to talk to people involved in the project. I’ve been to McDonnell Aircraft in St. Louis, where the capsule was made; to Houston, where the astronauts live; to the Martin Company near Baltimore, where the booster was built; to the Goddard Space Center. And I’ve been at Cape Kennedy for this week — talking, taking notes, reading. Then I sit down and write page after page of notes for my background material, organizing it chronologically — pre-launch, launch, orbit, etc. And then what happens is that after I’ve done all that, it’s all there in my mind.”

Look & act the part. A concern with appearance may seem antithetical to the virtue of gravitas. After all, isn’t it a function of depth over superficiality?

But gravitas is a trait that does not exist outside of its perception by others, and externals are the tool by which internal values are communicated. Clothes and demeanor can either enhance or detract from the “weight” one wishes to convey; think of the way a doctor’s coat or a police officer’s uniform plays a significant role in creating an impression of authority. Likewise, when a man is dressed like a schlub or an adolescent, people simply do not take him as seriously.

This was a conclusion Cronkite reached early in his career. To deliver the sober news, he needed to look like a sober man — a real professional — and he thus kept his mustache well-trimmed, his suits neatly tailored, and his shirts well starched — their French cuffs embroidered with his initials and held together by cufflinks made to look like the CBS “eye.”

Cronkite intentionally crafted his mannerisms to convey gravitas as well. Whether it was the lowering and raising of his distinguished eyebrows, or the removal and replacement of his glasses, he knew how to use such tics to produce a desired effect.

This was especially true of the way Cronkite spoke. While the average American talks at a rate of 165 words per minute (and fast talkers clock in at 200 words a minute), Uncle Walt trained himself to speak at a purposeful 124 words a minute during his broadcasts. This composed cadence added weight to his words, and made them easier for viewers to digest. He also made masterful use of the deliberate pause; rather than feeling the need to fill every moment of dead air with the sound of his own voice and the din of mindless commentary, he understood that silence is sometimes the most potent seasoning for speech. While covering an inauguration or the launch of a rocket, Cronkite knew that the best way to highlight the significance of the moment, was often to let it speak for itself.

From his clothes to his inflections, Cronkite knew how to cultivate the sense of presence so crucial to gravitas. As his friend Mickey Hart put it, “He was a voice shaman. He had a powerful aura. The voice, glasses, pipe — they were perfect totems.”

…But Not Yourself

![walter cronkite black white smiling]()

“Walter was really the class clown. He made us all laugh. He was serious in believing we couldn’t take ourselves too seriously.” –Andy Rooney

In and of themselves, all the ways mentioned above that Walter Cronkite took seriously his job/role/influence would not add up to gravitas. For as mentioned earlier, unadulterated seriousness paradoxically has the effect of making a man seem not uber-weighty, but extremely ridiculous. A man should be committed to grappling with the weightier matters of life, but if this wrestle is not accompanied by an ability to also see and appreciate life’s transience, absurdity, humor, and fun, it becomes hard, to, well, take him seriously. Such one-dimensionality reads as an overweening sense of self-importance, a paucity of perspective, that repulses rather than attracts — that diminishes rather than enhances influence; it’s hard to trust a man who can’t seem to see and appreciate a wide swath of the human experience, who can’t see his own foibles, and who doesn’t carry the sense that all things, no matter how seemingly important in the present, will one day pass away. Without a measure of lightness, the weighty man sinks like a stone.

Quick, think of a modern television newscaster on FOX or MSNBC who you can imagine laughing at themselves. Right, you can’t do it. Modern news networks are anchored almost exclusively by those who take themselves too seriously, and are thus a gravitas-free zone.

Cronkite, on the other hand, ran no risk of being entombed by his own heaviness. Despite the sobriety he brought to his broadcasts, he was far from an uptight prig; away from the cameras, he exuded an effervescence that kept him happily floating through eight decades of life, and a humility that leavened his weightiness.

By cultivating the following two traits, he followed the wise maxim of President Dwight D. Eisenhower: “Always take your job seriously, never yourself.”

Humility. Unlike many of his fellow newscasters, Cronkite never let his ego get too puffed up. Described well by Brinkley as “rigorously unpretentious,” he thought that journalism was an important business, but he didn’t mistake the importance of his work for his own personal importance.

Cronkite’s colleagues at CBS called him “the eight-hundred-pound gorilla” because his stature allowed him to get pretty much anything he wanted, and he was arguably one of the most powerful men in journalism, and the culture at large. But despite his outsized influence, and cabinets of awards, he never let it all go to his head; disposed to self-deprecation, he was fond of insisting he was “only a newsman” — just a conduit tasked with conveying current events. As Brinkley puts it, “He was that rare TV reporter who never tried to put himself over the story.” When Cronkite retired, Kurt Vonnegut wrote a tribute to the anchorman appropriately entitled, “A Reluctant Big Shot,” in which the author observed that “A subliminal message in every one of his broadcasts was that he had no power and wanted none.”

Cronkite’s humility was partly rooted in his recognition of his own limitations. While many other journalists seemed to be carried along to success by natural talent and intellect, as a college dropout, Cronkite thought of himself as a kind of tradesman — someone who had to work at his craft to stay on top. He took a practical, nuts and bolts approach to his career and life and thought more about how to do the job at hand, than about himself, declaring, “I never spent any time examining my navel. And I’m bored with people who do.”

Proud of the way he had started at the bottom of the journalism ladder and climbed his way all the way up, he always maintained a kind of blue collar mentality about his work. As Tom Brokaw wrote of his friend in Time magazine:

“I always had the feeling that if late in life somebody had tapped him on the shoulder and said, ‘Walter, we’re a little short-handed this week. Think you could help us on the police beat for a few mornings?’ He would have responded, ‘Boy oh boy — when and where do you want me?’”

This down-to-earth attitude kept Cronkite open to feedback; he appreciated when CBS executives gave him honest critiques and he insisted on reading all of the mail he received from viewers himself; when such a letter illuminated an error made or hit upon a sound piece of criticism, Cronkite would write back and own up to the oversight. He readily extended the same courtesy to the politicians he covered on his program, as this example from his biography illustrates:

“When the CBS Evening News accidentally misrepresented a comment that Governor George W. Romney of Michigan made regarding the Black Power movement, Cronkite quickly ate crow. ‘Your complaint was justified and our handling of the story was not,’ Cronkite wrote to Romney’s press spokesman. ‘It is neither justification nor rationale but only by way of explanation that the news service copy which carried the Governor’s statement buried the full text of the pertinent remark and our writer and editor missed it. I hope we made amends by seeking an interview with Governor Romney, which was used yesterday with the full text of his observation.’”

![walter cronkite dancing laughing with son in living room]()

A sense of humor and fun. Cronkite’s off-camera personality may come as a surprise to those who only imagine him as the buttoned-down CBS anchorman. Away from the studio, he was in fact a playful man, who loved kids, conversation (to the point of labeling himself a “hangoutologist”), going out on the town, dirty jokes, and having fun. He and his wife, Brinkley, writes, “lived for humor,” and Walt had a near-constant “infectious laugh” that “wasn’t coarse or hearty or even especially loud,” but “just had an amazing ain’t life somethin’ ring to it.”

If Cronkite’s never-ending laughter doesn’t fit the public image of him, members of his circle of friends don’t either. Uncle Walt palled around with Jann Wenner, the founder and editor of Rolling Stone magazine, the artist Andy Warhol, and was especially good friends with Mickey Hart, the one-time drummer for the Grateful Dead. Cronkite and Hart not only hung out, but played the drums together, regularly rocking out in the anchorman’s living room. Guests to the Cronkite home would invariably find themselves invited to participate in these drumming jamborees.

Another, if more expected of Cronkite’s friends, Andy Rooney, penned a piece which celebrated his fellow newsman’s zest for life:

“The greatest Old Master in the art of living that I know is Walter Cronkite. Walter works and plays at full speed all day long. He watches whales, plays tennis, flies to Vienna for New Year’s. He dances until 2 a.m., sails in solitude, accepts awards gracefully. He attends board of directors meetings, tells jokes and plays endlessly with his computers. He comes back from a trip on the Queen Mary in time for the Super Bowl. If life were fattening, Walter Cronkite would weigh 500 pounds.”

To have real gravitas, you’ve got to be able to appreciate and have experience with the full spectrum of life; you can’t live with one foot already in the grave. There’s a reason a guy like Hitler, who had serious purpose and principles (no matter how nefarious) aplenty, still didn’t exude gravitas, and rather came off as that most peculiar of species — the killjoy clown.

Be Steady and Reassuring…

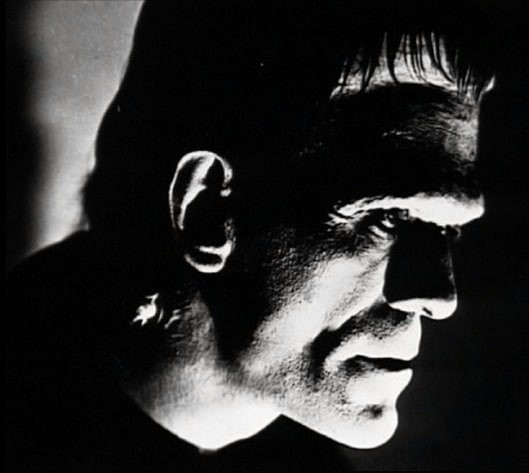

![walter cronkite close up of head face serious look]()

“A man lands on the moon. A president dies. Anything. If you can have one man in the world tell it to you, who do you turn on?

Cronkite.”

–Fred Friendly

“When our nation has been in trouble or made mistakes and there was a danger that our public might react adversely or even panic on occasion, the calm and reassuring demeanor and voice and the inner character of Walter Cronkite has been reassuring to us all.” –President Jimmy Carter, on the presentation of Cronkite with the Medal of Freedom

Whether a man has gravitas or not is most clearly revealed in a crisis. If he has it, he rises to the occasion; while others fall apart, his steadiness only increases — he’s the rock in the storm.

Think of a funeral. In such a situation, the man possessing gravitas is able to keep his composure; with compassionate poise, he delivers bad news; with great stamina, he unflaggingly takes care of what needs to be done; with a minister-like mien, he comforts the mourning; with the sagacity of a wise elder, he helps the grieving make sense of what happened. His is the gravitational force that holds people together. His is the healing hand on every shoulder. His is the presence that imparts reassurance and strength, a belief that life will go on. He is a human hearth that people naturally want to gather round.

Cronkite’s greatest exhibition of this steadying aspect of gravitas was unarguably in his reporting on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

On November 22, 1963, Cronkite was tasked with setting up a kind of televised grieving center, around which Americans could congregate to learn and process the news surrounding their slain president. At the helm of his anchor’s desk, Cronkite was part sea captain traversing the unexpected waves of the event, and part pastor, metaphorically reaching through the screen to place a reassuring hand on the nation’s collective shoulder.

His was the nearly single-handed responsibility of sorting through — in real time — the bulletins coming in, parsing which could be trusted, putting the various pieces of the story into a cohesive narrative, and determining when to deliver the final announcement of Kennedy’s death.

When that official news flash finally arrived, Cronkite struggled to maintain his composure as he made the pronouncement; his eyes moist, his throat tight, he removed his glasses, looked first at the audience at home, then at the clock on the wall to record and place the historic moment in time. Replacing his glasses, his voice still filled with emotion, he then proceeded to explain further details as then known.

Even though he “knew it was coming,” Cronkite later recalled of the bulletin, “still it was hard to say. It was touch and go there for a few seconds before I could continue.”

Continue he did, however, broadcasting for four hours before taking a break to commiserate with his family. He later returned to host the CBS Evening News as normal, and would continue to fill the anchor’s seat in the days that followed, offering the country marathon sessions of uninterrupted coverage and a constant, centering presence. His stamina, only surpassed later when he stayed on the air for twenty-seven of the thirty most crucial hours of the Apollo 11 mission to the moon, earned him the nickname “Old Iron Pants” among his colleagues. Cronkite shrugged off any praise for his endurance, however; as a professional, he said, you have a “job to do and you do the job.”

Cronkite always did his very best work — always exhibited his steadiest gravitas — when the pressure was on.

…As Well as Empathetic and Emotional

“When the news is bad, Walter hurts. When the news embarrasses America, Walter is embarrassed. When the news is humorous, Walter smiles with understanding.” –Fred Friendly

Though Cronkite’s gravitas was displayed through his ability to regain his composure while grappling with tragic news, it was also manifested in the fact that he struggled to keep it in the first place.

Gravitas isn’t unmitigated stoicism. A man made of impenetrable rock doesn’t convey depth, and is unable to offer comfort. It isn’t reassuring for someone entirely unfeeling to tell you everything is going to be okay; his words carry little weight because it’s clear he doesn’t understand the significance of the event or the loss. It’s similar to the way Aristotle says that a reckless man, who is heedless to risk, cannot really be courageous. It is consoling, on the other hand, to receive reassurance from someone who sympathizes with your pain, who’s feeling that pain too, but is still moving forward. He commiserates, but is able to carry the weight a little better than you at the moment, and thus points the way forward.

That was Cronkite to a T. As a friend described him, “He had an antenna sensitive to friends’ pain.” It was an antenna that extended to the pain of the country as a whole as well. While Cronkite was typically an exemplar of even-keel when the cameras were rolling, off the air, he allowed himself to feel things quite deeply.

After the broadcast in which he reported the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., he left this anchor chair and wept. He reacted similarly to the killing of Robert F. Kennedy. Hearing the news at home, he bolted out the door to get to the CBS studio as quickly as possible:

“I ran for a cab, buttoning my shirt on the way. The driver had his radio on. We were both just listening, speechless, I guess. Listening to the turmoil in that hotel kitchen, we cried. That cabdriver and I cried. We cried. And we weren’t ashamed.”

Cronkite perhaps sobbed most heavily after astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee — men he considered absolute heroes — died in the pre-launch test for the Apollo 1 mission.

The weight of gravitas, then, is composed of a balance of steadiness and emotion, control and compassion.

In our time, the free disgorging of emotion is seen as an unadulterated good — a tenet of psychological health. Self-expression is king. In fact, some feel that the emphasis on men keeping a “stiff upper lip” has stunted our well-being. Yet what is little understood about the traditional emphasis on masculine control, is that it was never about not feeling things, nor stifling their expression. Rather, a healthy stoicism simply means possessing the ability to choose when and where to air one’s emotions. Modern society doesn’t value this idea, because it’s based on another forgotten concept: honor. One temporarily puts aside one’s personal needs, in order to act as a strength and support to friends and family. Gravitas, then, is a generous, willing sacrifice, an act of service on behalf of others.

Be Opinionated…

A man with gravitas has deep convictions. Cronkite certainly did. Though he was registered as an independent, he leaned liberal and was an ardent supporter of the various equal rights movements of his day, as well as protecting the environment.

…Yet Maintain the Ability to Be Objective, Fair-Minded, and Flexible

“Walter is so objective, careful, and fair in his presentation of news that he has been characterized — if not immortalized — with the oft-heard line: ‘If Walter says it, it must be so.’” –William S. Paley

“We didn’t pick Walter because he was beautiful — he wasn’t. We didn’t pick Walter because a focus group, wired up to a machine, palpitated at the sight of him. They didn’t have things like that in those prehistoric days, so we were on our own. We picked Walter for the only sound reason to pick an anchor: He was a real pro, a superb reporter — a newsman who always gave his audience an honest account, no matter what his personal beliefs. It was the right assignment.” –Richard S. Salant, president of CBS News (1961–64; 1966–79)

Despite Cronkite’s decided opinions, he didn’t think a news broadcast was any place for them to be shared. Hewing to the motto, “If the World Goes to Hell in a Handbasket It’s the Reporter’s Job to Be There and Tell What Color the Handbasket Is,” he saw his role as anchorman as that of communicator, rather than editorializer, and unlike some of his fellow newsmen, he didn’t use the CBS Evening News platform to campaign for pet causes. His only agenda was to educate the public. “On television,” he explained, “I tried to absolutely hew to the middle of the road and not show any prejudice or bias in any way.” For this he earned the nickname “Mr. Center.”

Cronkite was so adept at playing things down the middle, that the public was often confused as to what his personal political leanings actually were.

After chairing his first Democratic and Republican National Conventions in 1952, Cronkite was initially concerned to receive letters alternately accusing him of being biased towards Eisenhower or biased towards Stevenson. “Then I came to a marvelous revelation,” he wrote a friend. “They were about equally divided between those who thought I favored the Democrats and those who believed I favored the Republicans! Since then, this has been my rule of thumb: If the charges stay in reasonable balance, I consider that I am succeeding in maintaining objectivity.”

If the public couldn’t sometimes discern where Cronkite’s partisanship fell, political candidates were often confounded as well. President Kennedy felt the anchorman had aired unfair coverage of him during the 1960 election, and thought Cronkite was a Republican. On the other hand, President Nixon, who had declared that “The press is the enemy” in a taped conversation in the Oval Office, regularly called out Cronkite by name in similar recordings.

Even when Republican presidents were aware of Cronkite’s liberal leanings, they still often respected his gravitas. Eisenhower chose Cronkite to do a series of extended interviews with him, which amounted to 13 hours of footage, to create the 3-hour special, “Eisenhower on the Presidency.” He likewise picked Cronkite to host “D-Day Plus 20 Years” in which the anchorman and the former general returned to Normandy to record Ike’s recollection of the historic event. Twenty years later, Reagan, who respected Cronkite as a “pro,” gave the newsman an exclusive interview in conjunction with the speeches he made in Normandy commemorating D-Day’s 40th anniversary. Both Eisenhower and Reagan knew that Cronkite — who had long campaigned for June 6th being honored as the central anniversary of WWII, and who had of course covered the war firsthand as a correspondent — was the only anchor who carried the weight necessary to properly mark the occasion.

It’s no wonder, as Brinkley reports, that “According to an informal poll, politicians of all stripes considered him the fairest of the national newsmen. Everyone of consequence, it seemed, thought Cronkite gave people an honest shake in interviews.”

Cronkite was not only known for his dependable fairness, but for his sympathy even for public figures he personally opposed.

Despite the antagonism Nixon had shown him, when the president resigned, Cronkite saw no reason to kick the man when he was down, and not only gave him a respectful send off on his broadcast, but also occasionally publicly praised the ex-president in the decades until his death — behavior liberal critics found befuddling and distasteful.

Similarly, though Cronkite celebrated the election of Bill Clinton, he felt great sympathy for HW and Barbara Bush, with whom he was on friendly terms, and who, Brinkley writes, he considered “among the finest, most patriotic people he knew.” When, a month later, Cronkite emceed the Kennedy Center Honors at which the lame duck president was in attendance, Walt “suddenly launched into an unscripted moment”:

“At the show’s close, he pointed at President Bush and offered a high note of thanks. ‘There’s one more honor to be paid tonight,’ he said, turning himself to look squarely at the president’s face, ‘to an individual who has served his country in war and peace for more than a half a century who has joined us again tonight to pay tribute to America’s performing arts. We offer him our respect, our gratitude, and we thank him for service to his country with honor.’ President Bush got a long standing ovation, with a grateful Cronkite the last to stop clapping.”

Pure Cronkite class.

Cronkite’s ability to see the good in folks on both sides of the political aisle, extended to his private circle of associates as well. His friends included plenty of liberals, of course, but decided members of the GOP establishment like Roger Ailes, John Lehman, and George Shultz as well, and he regularly went sailing with conservative writer William F. Buckley.

It wasn’t a struggle for Cronkite to bridge the divide; as Brinkley writes, “Rigid ideology and political correctness bored him.”

Cronkite’s objective, middle-of-the-road stance ultimately went a long way towards creating his outsize influence and centering presence, and garnering the widespread credibility he enjoyed with people of all ages and political parties. To many, he seemed refreshingly fair-minded, even-keeled, and able to deliver facts without the interference of personal feelings and biases.

Of course, non-journalists are not held to the same standard of objectivity, and even Cronkite, once he retired from the anchor’s chair, became much more outspoken about his political opinions. But for the private citizen who wishes to be a leader, this lesson in gravitas should still be heeded.

Shrill, rigid partisanship and gravitas are antithetical. No one wishes to confide in a stubborn ideologue, or turns to them for comfort, or willingly engages them in dialogue, because everyone already know exactly what they will say on every single issue. Wielding their opinions like a sword, they rebuff and divide people, rather than gathering and connecting.

To be sure, the passionate political or social crusader has a set of virtues of his own, and can bring together a certain set of people. But only gravitas is effective at unifying a wide spectrum of folks who might otherwise reside on different sides of an subject.

A man with gravitas, though he has strong convictions, is able see both sides of something, can understand another person’s perspective, is open to compromise, and can have reasonable, thoughtful debate with those with whom he disagrees. He doesn’t bludgeon people with his opinions, or even wear them on his sleeve, behavior which is supposedly a mark of passion, but really amounts to a lack of emotional control. Given this reputation for flexibility and fairness, such a man is widely respected, liked, and trusted by a variety of people, and his influence and importance greatly increase.

Be Rooted and Stable…

![young walter cronkite with family at piano]()

“Cronkite is not a genius at anything except being straight, honest and normal.” –Andy Rooney

“For an entire era, Cronkite was — and this is what psychologists say is the greatest tribute to a parent — there.” –David Shribman, The Washington Star

In many ways, Walter Cronkite was, in the parlance of the time, a real square.

Raised in Missouri and Texas, he evinced a kind of heartland-bred, genuinely decent, down-to-earth demeanor, and exuded a Midwestern, aw-shucks folksiness which was reinforced by his propensity to punctuate his speech with “gosh” and “golly.”

His living room drumming and night life loving aside, he earned a “lifelong reputation,” Brinkley notes, “for being a ‘company man’ at heart.” He was a rooted, stable guy, who felt loyalty to the organizations in which he worked, stayed married to his wife for 65 years, had three kids, paid attention to the details, showed up to work in his suit every day, and possessed a knack for management and business-like efficiency. The New York Daily News accurately described him as “Solid as a mountain,” and “As reliable as the sunrise.” His life and career were distinguished not by a string of controversies or scandals, but by the lack of them.

Despite his liberal leanings, he didn’t like hippies (“I didn’t like their attitude. I didn’t like their dress code. I didn’t much like any of it.”), political correctness, or in-your-face protests. He was widely read, but knew barely anything about current pop culture.

Uncle Walt was old school. Establishment. Seemingly unchanging.

And that’s not a bad thing.

Cronkite’s constancy is what imparted to him the omnipresent, pillar-like qualities of gravitas. He was a human institution — a patriarchal figure who seems like he’s always been there, and will always be there. You know a man has real gravitas when it’s hard to imagine your world without him around.

Yet stable dependability, by itself, does not beget this kind of “institutional” status. You surely know plenty of “squares” who are reliable as rain, but don’t convey any gravitas. Constancy’s gravitas-enhancing properties are only activated when it represents one side of a double-edged blade, with the other side being significantly edgier.

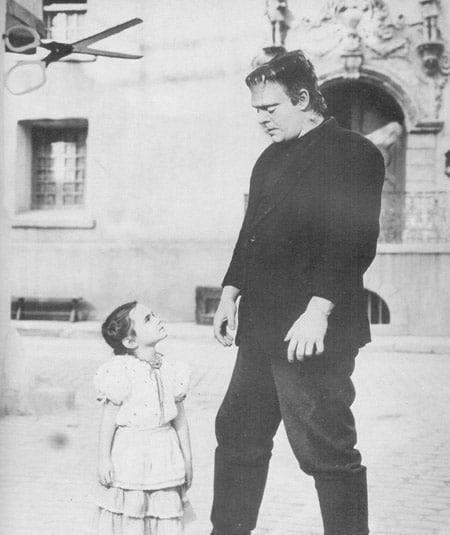

…Yet Willing to Take Risks, Accept Hardships, and Put Skin in the Game

![walter cronkite with soldiers in front of airplane]()

“Because everybody knew that Walter didn’t get his suntan in the studio lights. He got it from being out on the scene, story after story. And that’s why you liked to work for Walter. He knew that the news didn’t come in over the wire-service machine. That some reporter had to go out there, somebody had to climb up to the top of the city hall steeple to see how tall it was, somebody had to do that. Walter knew how hard it was to get news because he had been there.” –Bob Schieffer, on why Cronkite was so trusted

You may never have thought of Walter Cronkite as a guy with “a compulsion toward risky endeavors”; a man for whom “daring was the vital element of being.” But that’s just how Brinkley describes him.

So what is it about Uncle Walt you don’t know?

Before he settled into a domesticated anchorman routine, he spent seven years as a war correspondent and international reporter stationed in war-torn and austere locales.

When World War II broke out, Cronkite fervently wished to become a pilot, but discovered that his color blindness not only barred him from taking flight, but granted him a medical deferment from any kind of military service.

Young Walter could have stayed in his job working stateside for the United Press, but he decided to cover the war in the field, and left home in 1942 to become a correspondent on the frontlines of Europe. As a roaming reporter, he had to travel light, carrying only a duffle bag and his portable typewriter. Accommodations varied, from modest hotels, to flea-bitten dives, to outdoor campgrounds.

When the commander of the Eighth Air Force invited eight journalists to accompany the crews of B-17s and B-24s on bombing missions over Germany, Cronkite, despite the significant danger, jumped at the chance and successfully pressed to be chosen. He and the other members of the team — which became known as “The Writing 69th” — were given a week of training in first aid, parachuting, enemy identification, and even how to shoot the plane’s weapons (despite rules barring non-combatants from carrying a weapon into combat).

During the actual bombing run, Cronkite was tasked with manning the starboard gun of a Flying Fortress, and in fact end up firing at a German fighter during the course of the mission. Unfortunately, in terms of getting firsthand material for his reports, but perhaps fortunately for his longevity, Cronkite’s first bombing mission was also his last — when the B-24 carrying a fellow correspondent was shot down on the initial run, killing all on board, all future flights for the Writing 69th were canceled.

Cronkite went on to cover D-Day, Operation Market Garden (landing in a glider with the 101st Airborne), and the Battle of the Bulge. While most reporters, including the famous Edward R. Murrow, made trips back to the States during the course of the war, Cronkite worked for more than two years straight, rejecting, as Brinkley writes, a return to the “normalcy of hamburger cookouts, Clark Gable matinées, and the Andrews Sisters” to remain in the thick of the action, where history continued to unfold with life and death intensity.

At the end of the war, Cronkite was assigned to cover the Nuremberg trials in Germany, and then was made the UP’s main reporter in Moscow in 1946. There Cronkite’s wife, who he had been separated from her husband for several years, finally joined him. Together they lived for two years on a tight salary in a dilapidated apartment, until, tired from the deprivations of living abroad and Walt’s working seven years without a real vacation, they returned to the States to start a family and begin a more settled existence.

Though, truth be told, Cronkite never entirely gave up his thirst for adventure, nor his tolerance for hardship.

As a 52-year-old broadcasting celebrity, with a big salary and cushy lifestyle, he made a return to being a war correspondent in 1968 by traveling to Vietnam to investigate the conflict on the ground. Cronkite trekked to a U.S. Marine Corps base in the countryside and set about his research without demanding any special treatment. “Reporters working for AP, The New York Times, UP, and Reuters,” Brinkley writes, “were surprised to see the renowned Cronkite walking through the bombed-out streets of Hué, gunfire erupting in the vicinity, with the poise of a combat veteran. Like the younger correspondents, he slept on the bare floor of a Vietnamese doctor’s house that had been turned into a pressroom. He ate C rations and used the overflowing latrine. No one thought he acted like a bigwig or was bigfooting.”

After his retirement from the CBS Evening News, a 60-something Cronkite sought out special assignments that took him all around the world, from the wilds of Alaska to the Amazon river, where, after leaving his motorized dugout canoe for a quick dip, he got nibbled on by piranhas.

From youth to older age, then, Cronkite literally put his skin in the game for his work. Without these times of risk and hardship, his periods of stability and reliability would have lacked significance and been categorized as merely safe and pedestrian — a retreat to routine and comfort involuntarily made due to fear or inertia. But, because his stable periods were “earned,” so to speak, they became “activated” enhancements to his gravitas. They demonstrated an intentionally chosen reliability — a capacity to get down and do more staid but important work — based on real desire, rather than cowardice.

Conversely, if a man shows only a capacity for endless travel and adventure, but cannot ever dig in and show constancy in a commitment, then his propensity for risk fails to add to his gravitas. We may think that extreme athletes or adventurers are “cool,” but we rarely find them “weighty.” Often, they’re in fact of the flighty (pun perhaps intended) type.

It’s similar to the concept that “you have to be a man, before you can be a gentleman.” Stability and constancy enhance one’s gravitas if you’ve proven you also have a harder edge. And once you do hone that flintier side, you still must progress on to show you can be fully there for something, or someone.

Be Skeptical…

![walter cronkite in war zone wearing helmet and vest]()

“He had this great curiosity. If there was a car wreck and Walter saw it, it would be like the first car wreck he’d ever seen in his life. He’d want to know all about it.” –Bob Schieffer

The weight of gravitas rests on a foundation of truth, a truth which can only be discovered through serious-minded sifting and objective judging of evidence.

That was Cronkite’s M.O. He was not a man who suffered fools lightly. Curious, savvy, and skeptical, a fellow reporter described him as having a particularly “sensitive shit-detector” and Brinkley observes that “No one knew how to separate the chaff from the grain quite like Cronkite. Seeing through shell games came naturally to him.”

Central to this sifting task, was sussing out the facts of what was really going on in the world, something for which Cronkite had an absolute passion. “Find the Facts” was one of his favorite phrases, and he couldn’t rest when he was hot on their trail. He had an insatiable desire to get to the bottom of things and find out the truth, and was, as Brinkley writes, possessed by a “tyrannical demand for answers.”

The search would not stop with the verification of one or two sources. His early journalism mentors had taught Cronkite to triple check everything, and to wait to make pronouncements until confirmation had been received through the most reliable channels — mainly the Associated Press and United Press wire services. “He took nothing for granted,” remembered Don Hewitt in his memoir, Tell Me a Story. “He picked up the phone and checked with people he knew would give him a straight answer and, at the same time, throw in a couple of facts that made his reporting better than anyone else’s.”

Cronkite’s most famous fact-finding mission came in 1968, when he made his aforementioned trip to Vietnam in the aftermath of the Tet Offensive. In the early years of the war, he had maintained a neutral to supportive view of the conflict, and largely based his reports on official reports coming out of the Pentagon. But the things he was hearing from reporters on the ground in Vietnam increasingly belied the more optimistic statements being issued by President Johnson and the military’s top brass. Cronkite wanted to see for himself what was really going on.

When he arrived in Vietnam, he deliberately avoided spending his time around the official press conferences, as he had done on a previous visit. Instead, he traveled into the South Vietnam countryside — positioning himself in the thick of the action and making his way to remote military outposts. “Like a prosecuting attorney gathering facts,” Brinkley writes, “he interviewed everyone, from orphans to traumatized U.S. soldiers. He went on a marine patrol to survey the perimeter roads around Hué. According to him, he was only operating on a Journalism 101 principle learned in high school: the more information, the better the story.”

From his wide-ranging, in-the-field research, a different picture of the war than the one being presented back home soon emerged. After returning to the States, Cronkite presented the public with what he had learned in the aptly titled special report: “Report from Vietnam: Who, What, When, Where, Why?” and famously concluded that rather than winning the war, the country was “mired in a stalemate.”

It was one of the few times Cronkite departed from his commitment to complete objectivity (and he intentionally offered his commentary during the special report, rather than on the CBS Evening News, where objectivity was sacrosanct). “I did it because I thought it was the journalistically responsible thing to do at that moment,” he later explained.

…But Also Sincere

![walter cronkite with dwight eisenhower at arlington cemetery]()

“There’s something in Walter’s style, his character, his very face and delivery that promotes sincerity.” –Chet Huntley, NBC news anchor

“[Cronkite] remains as entranced by the unfolding of each day’s news as a child with a new kaleidoscope.” –Kurt Vonnegut

Even though Cronkite was a stickler for facts, his inherent skepticism never devolved into entrenched cynicism.

Cronkite felt a genuine passion for some of the issues he covered, which could create a weakness in maintaining his objectivity, but largely worked to strengthen his gravitas overall.

In the same way that steadiness must be punctuated by emotion to demonstrate real depth, skepticism must be matched with sincerity to achieve the same effect. A strain of pure enthusiasm maintains gravitas’ qualities of reverence and solemnity — qualities that require a bit of unadulterated awe.

It was in fact partly Cronkite’s unabashed support for the troops that kept him from changing his mind about Vietnam for so long. Though he had encountered danger as a correspondent during WWII, the risk paled beside that shouldered by the soldiers in the trenches and the flight crews in the sky, and the experience left him with a sense of both guilt and humility, as well as an indelible reverence for members of the military.

While this conviction biased him during WWII towards making reports that sometimes bordered on patriotic propaganda, and may have colored his early reporting on Vietnam, at the same time it lent him the depth of feeling needed to properly commemorate the aforementioned anniversaries of D-Day, and connect with the many veterans who attended the events. Of walking silently with Eisenhower past the 9,000 graves laid out at the American cemetery near Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, Cronkite said, “It may have been the most solemn moment of my career.”

When twenty years later Cronkite found himself back in Normandy with Reagan, “Everybody [veterans] wanted to keep shaking Walter’s hand,” a colleague remembered. “They were moved to tears by the mere sight of the old anchorman returning to Pointe du Hoc.”

Cronkite’s patriotism extended beyond the troops, to his country as a whole; he was an unashamed flag waver. Cronkite got to give full expression to his love for America during the nation’s celebration of its bicentennial in 1976. Brinkley notes that “When Cronkite heard ‘Amazing Grace’ — his favorite song — played on bagpipes that special Fourth of July from the Mall, he wept openly.” Uncle Walt infused his broadcasts of the nation’s 200th birthday with a full-throated enthusiasm, sincerely believing the celebration could serve as “the Great National Healing” and “was exactly what America needed after Vietnam and Watergate. Cronkite used the bicentennial to tell Americans it was alright to be proud of their country again.”

Cronkite’s most genuine ardor and gee whiz excitement, however, was reserved for the nation’s space program. He was, in Brinkley’s words, “a huge cheerleader for NASA” — an evangelist for what he called the “conquest of space.” The idea of hurtling up to the stars, landing on the moon, and eventually journeying onward to visit our solar system’s planets, fired Cronkite’s imagination, inspiring him to make rhapsodic pronouncements like, “Of all humankind’s achievements in the twentieth century and all our gargantuan peccadilloes as well, for that matter — the one event that will dominate the history books a half a millennium from now will be our escape from our earthly environment and landing on the moon.”

Cronkite still believed in heroes, and the astronauts willing to make that escape were his — he lionized them as courageous, modern-day explorers.

The anchorman’s admiration and awe for the space program memorably infused his broadcasts of mission launches. The launch of a rocket could alternately leave him speechless, or find him shouting with boyish glee: “Go, baby, go!”

When the Apollo 11 spacecraft left earth, Cronkite spent several seconds in silent reverie, before exuberantly exclaiming: “Oh boy, oh boy, it looks good…Building shaking. We’re getting the buffeting we’ve become used to. What a moment! Man on the way to the Moon! Beautiful.” And when “the Eagle” finally landed, Cronkite celebrated the moment with tear-soaked eyes, and an awe-struck “Oh, boy!”

Cronkite’s authentic elation and admiring reverence perfectly matched the drama and gravity of the event, while his serious knowledge of the spacecraft’s mechanical workings and physical dynamics steadied nerves with the words of authoritative expertise. Together these qualities allowed Uncle Walt to triumph over his much drier anchor rivals and become the go-to guide for the millions watching the Apollo 11 mission around the world — many of whom barely took their eyes off Old Iron Pants’ face during his hosting of nearly 30 hours of live coverage.

Yes, Cronkite’s sold-out zeal for cosmic exploration kept him from being entirely objective about the value of the space program, and his childlike delight in it might on paper seem to detract from the seriousness of the mission. But, once again, a tempering force, in this case, sincerity and heart, actually enhanced rather than detracted from Cronkite’s gravitas — adding weight and depth to what might have otherwise been a merely stony and superficial summary of such historic events.

Conclusion

![older walter cronkite with tobacco pipe]()

Gravitas, if it’s thought of at all, is often imagined as something monolithic. But while its core of integrity must be unadulterated, the virtue is in fact made up of multi-faceted aspects — pairs of traits that provide a necessary counterbalance to each other. You can’t just take everything extremely serious, and hope to develop gravitas. Rather, you must temper solemnity with humor and humility; stoic steadiness with emotion and empathy; skepticism with sincerity; stability with risk; conviction with flexibility.

The equation of gravitas comes down to something like weight X depth. You can’t only add to the weight while ignoring the depth, nor vice versa. The first scenario would create a life akin to a flat, heavy stone. The second would be like unto a flimsy hole. Either way, a one-dimensional character is brittle, fragile, and prone to fracture.

Trust and respect comes to the man with perspective and self-awareness, warmth and toughness, dependability and courage — a man who can shoulder important responsibilities with purposeful seriousness…and also laugh at himself and the absurdity of life.

In possession of such gravitas, a man cannot only authoritatively sign off to things with Uncle Walt’s classic catchphrase: “And that’s the way it is”…

…but people will really believe him when he says it.

_______________________

Source

Cronkite by Douglas Brinkley

The post Lessons From Walter Cronkite in the Lost Art of Gravitas appeared first on The Art of Manliness.

Being part of the resistance was incredibly dangerous and required putting one’s life at stake. Historians estimate that only 2% of the French population became active resistors, and of those willing to participate, Lusseyran observed that four-fifths were less than thirty years old:

Being part of the resistance was incredibly dangerous and required putting one’s life at stake. Historians estimate that only 2% of the French population became active resistors, and of those willing to participate, Lusseyran observed that four-fifths were less than thirty years old: